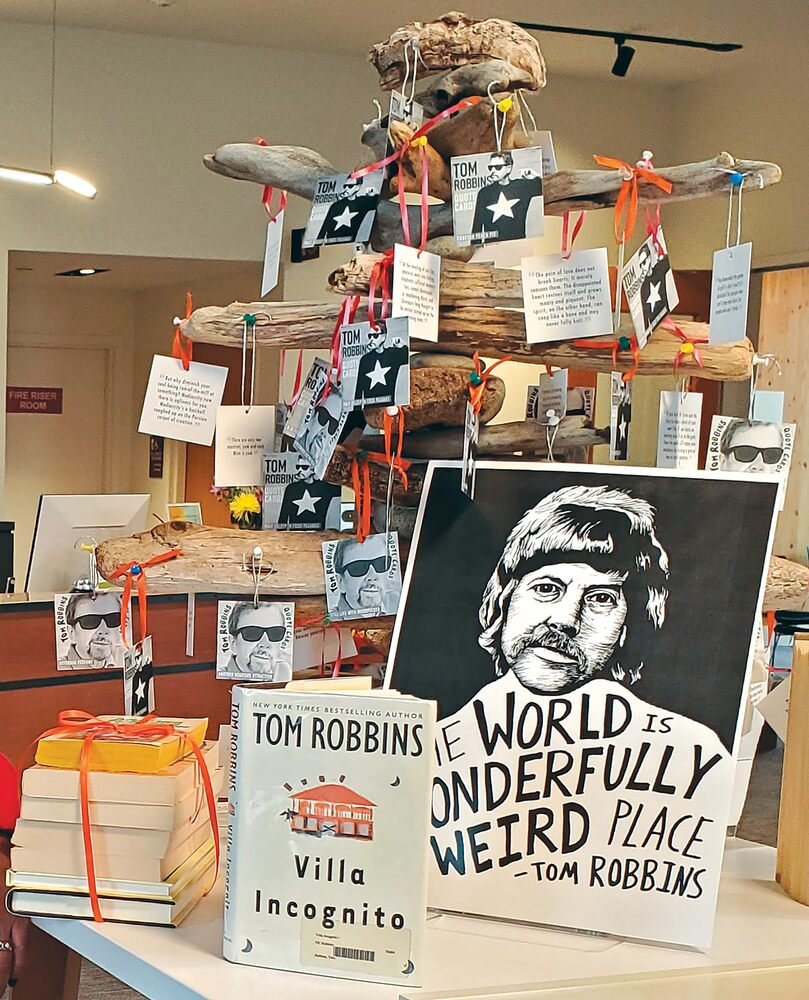

Tom Robbins, for a very long time, held the undisputed top spot as my very favorite writer. Over the years, as my personal library has expanded and I’ve discovered new and interesting writers, Robbins has had to share his top spot and, on rare occasions, he's even had to give it up (to writers like Jasper Fforde or Tim O’Brien) depending on which book I've just finished reading. No matter what, he’s always on my short list and, if forced to make a decision, he stands a 90% chance of being named Martin’s Favorite Writer™ (I just made up that statistic, but it feels true).

I've read all but two of Tom Robbins’ novels (B is for Beer and, arguably his most famous novel, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues) and he never ceases to be entertaining. I’m slightly torn as I write this post, because, I keep thinking I should be writing about Skinny Legs and All or Jitterbug Perfume, my two favorite Tom Robbin's novels. But, because Robbins has had such a profound influence on me and my writing, it stands to reason that I should write about the first novel of his that I ever read: Still Life With Woodpecker.

I was about 19 years old the first time Tom Robbins was brought to my attention. I was heading out to LAX with my dad for a week-long trip to Louisiana and, hoping to disuade me from reading Stephen King's Insomnia on the flight over, my brother, Greg, told me I should instead read Even Cowgirls Get the Blues. His plan might've worked, if only he'd actually had a copy of the book with him at the time. But, alas, he did not and off to Louisiana I went sans Tom Robbins.

About a year or so after that trip, while hanging out at the Ontario Mills Mall, I went into Foozles—an outlet bookstore that, unfortunately, closed down not long after it opened—and happened upon a shelf of Tom Robbins books. Because Tom Robbins had seemingly settled into my consciousness, I felt obliged to pay him a little attention. I picked up Skinny Legs and All and read the first page or so. I was both impressed and amused with Robbins’ prose, but, being that I was in the middle of the mall, I couldn’t very well settle into it, so I put it back and went on my way.

Not long after that, while hanging out at Greg's house, I went to his bookshelf and discovered he had quite a few Tom Robbins novels. I picked up Half Asleep in Frog Pajamas and, upon reading the first page or so, found myself thoroughly impressed with how easily he opened the story with unique wit and charming prose (I specifically remember wondering if I'd ever be able to write novel with such an opening). And yet, like Skinny Legs and All before it, I put the book down, without any real intention of picking it back up again.

At some point, a few months later, I was staying with Greg for an extended visit. During my visit I went back to his bookshelf and, wanting to peak into another Tom Robbins novel, I randomly picked up Still Life With Woodpecker. In the Prologue, Robbins is telling the reader—and, seemingly, himself—about his new typewriter, the Remington SL3.

"I sense that the novel of my dreams is in the Remington SL3—although it writes much faster than I can spell. And no matter that my typing finger was pinched last week by a giant land crab. This baby speaks electric Shakespeare at the slightest provocation and will rap out a page and a half if you just look at it hard.

'What are you looking for in a typewriter?' the salesman asked.

'Something more than words,' I replied. 'Crystals. I want to send my readers armloads of crystals, some of which are the colors of orchids and peonies, some of which pick up radio signals from a secret city that is half Paris and half Coney Island.'

He recommended the Remington SL3."

-Tom Robbins, "Still Life With Woodpecker"

Because I'd be staying with Greg for a few days, I allowed mysel the treat of reading on and, one sentence at a time, I fell madly in love with Tom Robbins (just now, as I was writing that last sentence, I considered clarifying that I hadn’t fallen in love with Tom Robbins specifically, so much as his writing, but decided that, really, they’re probably one in the same). Even when he's being interviewed, Robbins' thoughts about the world always fascinate me, as when he responds to a question about a typical day in his life.

"Since I try to avoid routines, I’m not sure I have a 'typical' day. When I’m off the road and working on a book, however, I do go to my writing room rather faithfully at 10 each morning, remain there until mid-afternoon (whether or not the muse elects to join me), with a noonish break for a solitary lunch. Afterward, there’s frequently a three-mile-walk followed by reading, yoga, dinner and all manner of tomfoolery, both legal and forbidden, familiar and arcane."

-Tom Robbins (from an interview in "Malibu Magazine")

I had only been reading novels for pleasure for about a year or two when I started Still Life With Woodpecker and, up to that point, I was under the impression that the prose side of writing was simply a necessity for telling the story. I had no idea before reading Still Life With Woodpecker that the prose could be every bit as entertaining as the story itself and sometimes, as is often the case in a Tom Robbins novel, even more so.

While Tom Robbins is something of a philosopher with loads of interesting opinions and insights into the world around him, it’s his unique way with words that I love most. Robbins is like a literary acrobat, doing things with words that I could never have imagined.

"The moon was full. The moon was so bloated it was about to tip over. Imagine awakening to find the moon flat on its face on the bathroom floor, like the late Elvis Presley, poisoned by banana splits. It was a moon that could stir wild passions in a moo cow. It was a moon that could bring out the devil in a bunny rabbit. A moon that could turn lug nuts into moonstones, turn Little Red Riding Hood into the big bad wolf."

-Tom Robbins, "Still Life With Woodpecker"

The writing was so playful and fun that the story being told became secondary; but even still, Robbins always has an interesting story to tell which, like his prose, is playful at worst and enlightening at best.

I even became convinced that, in my own writing endeavors, the story didn’t matter at all, so long as the prose was fun and interesting. It turns out that this isn’t true. At all. I wrote quite a few bad short stories before I realized it, but eventually, with the help of a terrific creative teacher, I figured it out. The story does matter and, despite his love of words, Tom Robbins knows this as well.

The story in Still Life With Woodpecker is about a princess named Leigh-Cheri, who is a former cheerleader, a liberal, an environmentalist and a redhead. She meets, and eventually falls in love with, Bernard Mickey Wrangle, also known as The Woodepecker, who is an outlaw, a bomber...and a redhead. My memory of the story involves an engaging love affair between the two, as well as interesting stretches of philosophical dialogue and long meditations on the power of a carton of Camel cigarettes (something to do with pyramids, as I recall). There is also a lot of talk about redheads and their supposed origin planet called Argon. It’s all very wild and interesting, but, ultimately, Still Life With Woodpecker is a love story.

"Albert Camus wrote that the only serious question is whether to kill yourself or not. Tom Robbins wrote that the only serious question is whether time has a beginning and an end. Camus clearly got up on the wrong side of bed, and Robbins must have forgotten to set the alarm. There is only one serious question. And that is: Who knows how to make love stay? Answer me that and I will tell you whether or not to kill yourself. Answer me that and I will ease your mind about the beginning and the end of time. Answer me that and I will reveal to you the purpose of the moon."

-Tom Robbins, "Still Life With Woodpecker"

I didn’t finish reading Still Life With Woodpecker during my stay at Greg’s, but I did take it home with me. By the time I was done I was hooked. I wanted more Tom Robbins. Incidentally, this new love affair of mine coincided with my first debit card and the immersion of Amazon.com. I searched out Tom Robbins novels, buying one at a time, never bothering to read the synopsis—never wanting to know what it was about—having complete faith that whatever was on the page would satisfy my jonze.

Armloads of crystals, indeed.